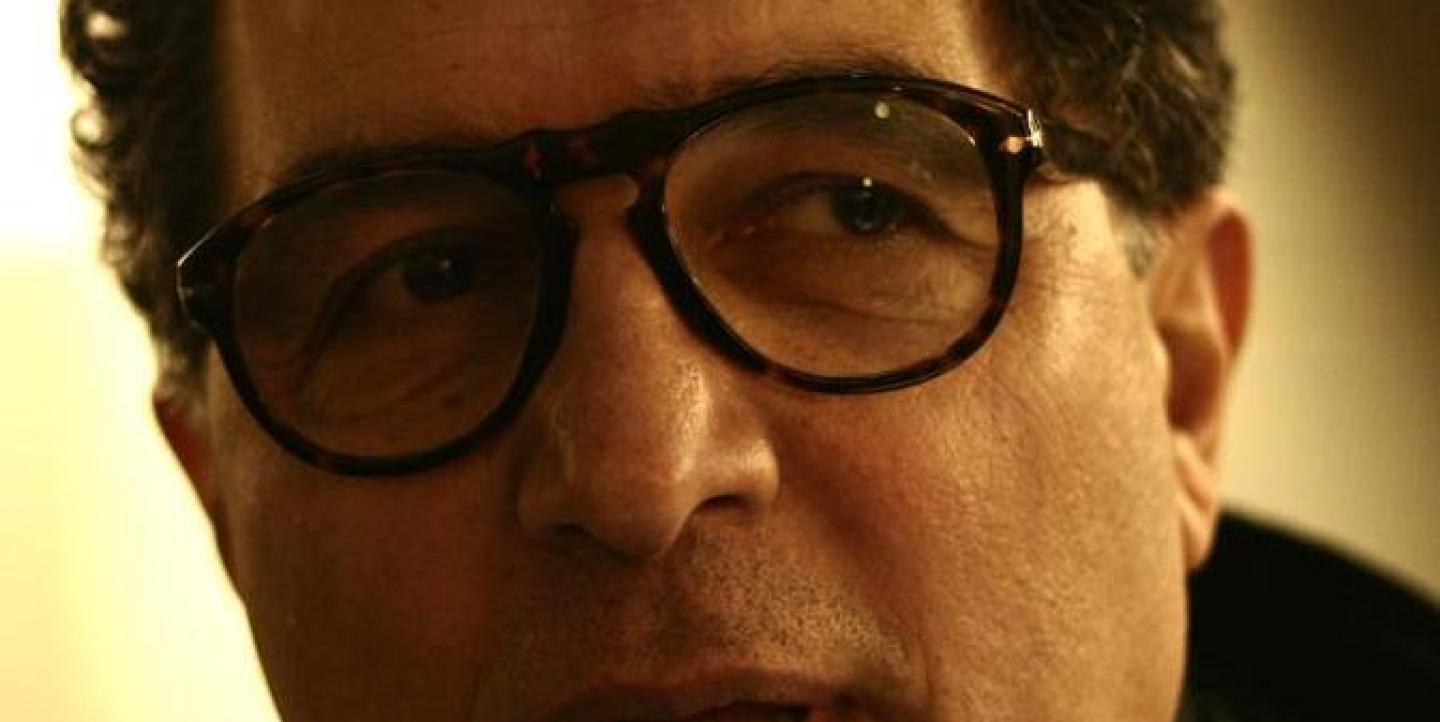

Seasoned Iranian journalist Masoud Behnoud recently shared with IJNet his thoughts on journalism ethics. A journalistic code of ethics should be universally accepted, Behnoud said, but often a lack of democracy in society influences journalists' respect for such ethics.

During his 44 years as a journalist, Behnoud has written over 15 books and produced eight feature films, 180 TV programs and 300 radio programs. He currently lives in the UK and works as a freelance journalist.

IJNet: What are the most important ethical principles for a journalist?

MB: First, we should find an answer to the question "For whom and why do we write?" Second, we should define how we are going to reach that answer. I always advise students and would-be journalists to come up with a definition of journalism first. Since Iran is [not a democratic nation], we can hardly reach the same definition of journalism as in democratic countries. They would, thus, reply that journalism intends to define the relationship between states [governments] and nations and journalists work somewhere in between. This definition is not applicable all over the world, but in countries where states have the final say in everything, it makes sense. In such societies, journalism ethics hugely determine content quality. Journalists must try to define their place vis-à-vis the society's norms and culture and the relationship of power with media so that they can safeguard journalism ethics and honesty.

IJNet: So standards of ethics depend on state regulations?

MB: Governments, especially in undemocratic nations, can influence journalism ethics because they have brute force and money. They can manipulate journalists via these perks. They can also have media ethical codes altered by prosecuting and imprisoning journalists. One study indicates that about 50 percent of Iranian journalists have been jailed at least once, a far cry from the number of their colleagues who are put in prison in other countries. And that number has increased over the last decade. These governments try to superimpose their ideal ethical codes on the press with both carrots and sticks. Even journalists working in state media, however, do their best to elbow away this top-down approach to ethics. In Iran, media ethics is not enshrined in a charter or manifesto. It is an amorphous mélange, manifesting itself according to the above-mentioned factors.

IJNet: After an interview, a source may ask a journalist not to publish a particular part of what he said. Some journalists argue that such requests should be ignored, unless the interviewee indicated his comments "off the record" during the interview. Which practice is appropriate?

MB: We should deal with these problems case by case. The car driven in Iran might be the same model driven in other countries, but its driving codes are distinct. That holds true for journalism. Due to Iran's religion-based culture, authorities imagine media as some sort of a monologue, in which they prefer one-way traffic. They prefer not to be scrutinized or answer any questions. This mentality affects the practice and values of journalism in Iran. You often hear the President and other officials complaining the media misquoted them. This often happens when the official said something irrational. If you are a Japanese, American or European official, you might apologize and repent. But in Iran, the officials shut down the newspaper and jail the journalist. Journalism ethics, therefore, are based on factors that can hugely affect journalists' lives.

IJNet: Are journalism ethics universal or local?

MB: Journalism ethics, just like human rights, are universal. They evolve as a society steps toward democracy. There are some universal codes that must be respected in every society. But as I said earlier, journalism ethics manifest differently in different places. The difference depends on the level of democracy in the country. In pre-democracy societies, these codes are yet to be institutionalized.

IJNet: What is the relationship between democracy in a society and journalism ethics?

MB: There is a direct link. The more a society shuffles toward democracy, the more its journalism ethics would seem like global criteria and standards and vice versa. In such nations as North Korea and Zimbabwe, discussing journalism ethics would sound impractical. It was the same in Iraq during Saddam Hussein’s government. But now, even though a war is still raging in Iraq, journalists can abide by ethical codes in the country.

IJNet: Given the current situation in Iran, how can Iranian journalists respect journalism codes?

MB: Iran is a country transitioning towards democracy, which is why you can see tension in every aspect of life. The conservative establishment tries to block the transition, but the modern population defies the block. Journalism ethics are one of those aspects. In recent years, female Iranian journalists have actively covered sensitive issues such as stoning and female executions. They brave imprisonment risks to draw public attention to these issues of women rights. They recognize these issues as newsworthy. This is part of journalism ethics since apart from who likes what, you cover the story because it affects many people's lives. These journalists go and talk to inmates on death row. I know instances where a journalist did not cave in to her editor-in-chief's pressure to reveal her sources and therefore was sent to prison.

IJNet: You said over 50 percent of Iranian journalists have been detained at least once. Can we conclude that journalists are ready to pay this price to protect universally accepted ethical codes?

MB: Definitely! The Iranian journalism community has made a lot of sacrifices to guard its ethical codes. During Iran's century-old march towards democracy, journalists have been killed both on the streets and in prison. Even those journalists working for state-owned media are aware of this struggle. A journalist who tasks himself with defending people would inevitably accept the trade's ethical codes, or at least part of them, no matter what external factors weigh in. He has to be honest in his stories because ethics are the essence of this job. Young journalists should be aware that besides content quality, their biggest challenge is how to settle on a set of principles that make their work meaningful. Whether in the U.S. or Iran or other countries, observing these principles and remaining loyal to them might be costly in the short-term, but journalists will eventually manage to establish themselves as professionals.