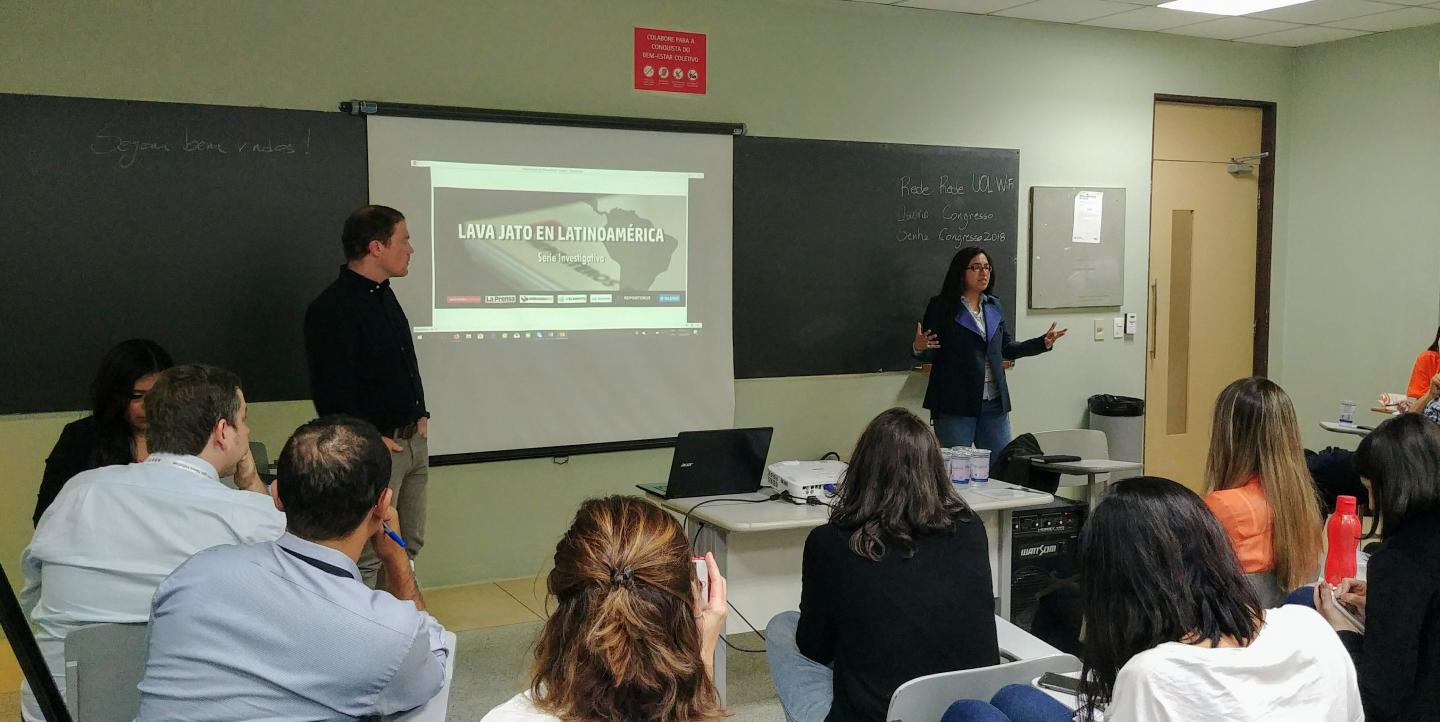

Collaborative journalism was the highlight of the panel "From Brazil to the world: Lava Jato's transnational coverage," which was part of the 13th International Congress of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji) on June 29 to 30 in São Paulo.

During the panel — moderated by John S. Knight fellow Guilherme Amado — panelists Romina Mella from IDL-Reporteros, Joseph Poliszuk from Armando.info, Milagros Salazar from Convoca and Flávio Ferreira from Folha de S. Paulo offered insights on the Lava Jato (Car Wash) investigations in Brazil, arguably one of the largest corruption scandals in history.

To reveal a corruption and money laundering scheme that involved businessmen and politicians, not only in Brazil but around the world, journalists in Latin America, the United States and Africa have united to launch two international consortia: Investiga Lava Jato and Lava Jato en Latinoamerica.

"We know that corruption is transnational, so journalism should be that way, too,” said Mella, one of coordinators of Lava Jato en Latinoamerica. “We decided to create a horizontal collaborative network of journalists, not media organizations, to investigate the [Lava Jato] case."

Salazar, who is responsible for the Investiga Lava Jato project in Peru, argued that consortia are a way to inform the public about big issues that are happening in their countries or issues outside the region that have a direct impact on their daily lives.

"It's easier for independent journalists than for large media organizations because they often have common interests with those they report on," said Salazar.

Collaborating is also a way to shed light on what was once left unreported.

"In the Lava Jato case, for example, during the analysis of the documents we would notice the name of a person from another country. We’d think, 'How can we embark on this story if we don't know anyone in this place?' How many stories were lost because we don't know someone who could focus more attentively on the subject?," said Ferreira, Investiga Lava Jato consortium’s coordinator in Brazil.

The amount of information involved with this type of reporting is another factor that justifies a collaborative model. As society demands more transparency of other bodies and entities, which results in an increasing amount of data to be processed.

Many journalists, especially those specializing in big data investigations, understand that a single person is not able to tackle all the analysis alone. The Panama Papers investigation, for example, led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), brought together hundreds of journalists from various news organizations and countries.

Building trust

Because big data deals with a lot of information, it’s important that the projects are well-coordinated and organized, and that communication is strong between team members. Additionally, all countries must agree on how the news will be made public since its access will take place in different ways depending on the country and type of publication.

"We have an agreement on when we are going to publish the information," said Salazar. "You have to understand the context of each country to establish a methodology for the work and publication."

Ferreira agreed with Salazar: "A colleague in print media might have less space in a few days than the digital one, and that will impact when the information will be jointly published."

In this scenario, trust is fundamental to building a successful consortium. "It is very important that professionals get to know each other in person in order to establish bonds. It boosts teamwork," said Carla Miranda, a journalist at O Estado de São Paulo, who authored the doctoral thesis "Collaboration in Journalism: from the Arizona Project to the Panama Papers" and participated in another panel at the conference.

Building trust allows the team to learn the strengths of each team member. It also gives them a chance to learn the similarities and differences in the coverage, legislation and other more of each country.

"In Brazil, the justice system works relatively quickly compared to other places,” said Mella. “Although some countries such as Peru, Argentina, Panama and Ecuador have initiated a series of fiscal lawsuits, in countries like Venezuela there is absolute judicial impunity."

A matter of safety

The impact of journalism partnerships is beyond media coverage. Countries in which democracy is not well consolidated, or nonexistent, benefit from collaborative journalism.

"These investigations protect us publicly," said Poliszuk, member of Lava Jato en Latinoamerica.

"Collaborative activities are important to protect the integrity of professionals [in countries] such as Mexico and Brazil where attacks on journalists are common," Miranda said. She stated that Brazil has one of the highest incidents of crimes against media professionals. Brazil appeared in eighth place on the Committee to Protect Journalists' Global Impunity Index and is ranked 102nd on the 2018 World Press Freedom Index, published by Reporters Without Borders.

"This type of work allows that, if journalists are persecuted in a country, their colleague is able to give visibility to the issue in another country," Miranda said.

Kalinka Iaquinto is a reporter and communications coordinator for independent news agency Eder Content.

Image of the presentation of Romina Mella (IDL-Reporteros), courtesy of Kalinka Iaquinto