On November 9, Eric Tucker, co-founder of a marketing company in Austin, Texas, tweeted about buses crowded with people paid to protest against President-elect Donald Trump. The tweet went viral nationwide. With just 40 followers, Tucker’s message was retweeted 16,000 times and was shared more than 350,000 times on Facebook. Although Tucker’s tweet brought controversy — and even caught the president-elect’s attention — no such buses ever existed. According to The New York Times, a company called Tableau Software hired the buses for a conference.

Two days later, a fake news site called The Denver Guardian spread across Facebook with negative and false messages about Hillary Clinton, including a claim that an FBI agent connected to Clinton’s email disclosures had murdered his wife and shot himself.

Fake news has become a problem that the media and technology industries are urgently searching for ways to solve. As a result, “the mainstream media has lost credibility even when it deserves it,” Dustin Siggins, a conservative journalist, said.

The problem has been growing for some time, but the presidential campaign turned a spotlight on this viral disinformation. In fact, fabricated stories drew more engagement on social media than real news as the elections drew to a close. In particular, fake news — that is, hoaxes, false and misleading stories from illegitimate sources — took advantage of the widening gap between booming tech platforms and legacy media companies. Facebook in particular has suffered the brunt of the criticism for allowing stories filled with factual inaccuracies to flood pages and misinform the public. According to Pew Research Center, nearly 1.2 billion people log on to Facebook every day; nearly half of Americans rely on the social network as their primary news source.

Mark Zuckerberg, chief executive of Facebook, deflected responsibility for the fake news epidemic away from his company, claiming that “identifying the truth is complicated.” Columbia Journalism Review found that it may be complex for algorithms but easy for journalists whose daily duty is as simple as investigating what happened, when it happened, who did what, how and why. Media literacy has become a challenge because people have grown so distrustful of institutional media that they turn to alternative sources. A Pew Research Center Survey found that only 18 percent of people have a lot of trust in national news organizations, nearly 75 percent said news organizations are biased.

Although Zuckerberg dismissed the idea that fake news significantly influenced voters in November, Facebook has nonetheless mounted its most concerted effort to combat the problem. Facebook announced it had begun a series of experiments to limit misinformation on its site. The tests include putting warning labels on fake news posts, making it easier for its 1.8 billion members to report fabricated stories, and creating partnerships with outside fact-checking organizations — including FactCheck.org, Google, The New York Times, PolitiFact, the Associated Press and CNN — to help it indicate when articles are false. “Below the headline there will be a red label that says, ‘disputed by third-party fact-checkers,’” Facebook Vice President Adam Mosseri said in a blog post.

News organizations are also investing in cutting-edge technology to battle for audiences’ trust and legacy using various ways that help the reader distinguish a real story from crafted one.

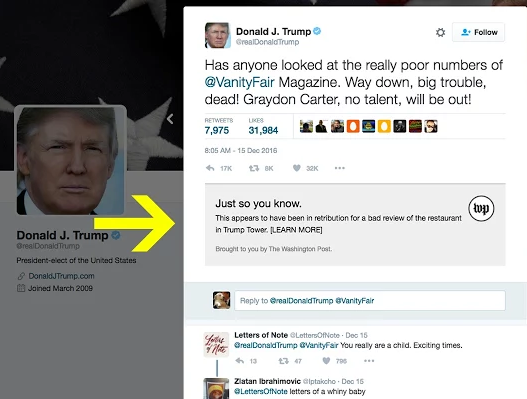

The Washington Post has created a Google Chrome extension to fact-check President-elect Trump's tweets. Trump, who uses Twitter like no other U.S. politician before him, discusses topics ranging from the political to the personal — but not all of his tweets are entirely accurate.

The Washington Post has created a Google Chrome extension to fact-check President-elect Trump's tweets. Trump, who uses Twitter like no other U.S. politician before him, discusses topics ranging from the political to the personal — but not all of his tweets are entirely accurate.

The Washington Post said the extension was built “to help ensure that the public receives the most accurate possible information by creating this extension, which will add more context or corrections to things that Trump tweets.” When the extension is active, a fact check box will appear directly beneath any given tweet.

Among other new filtering policies, Google promised to replace the “In the news" section that sits atop all desktop Google search results with a rotation of "Top stories." Google Spokeswoman Andrea Faville was not clear on how the company will determine the difference between false and accurate information going forward. “We use a combination of automated systems and human review,” she told The Washington Post.

Slate has also built “This Is Fake,” a free Google Chrome extension that both identifies articles in Facebook feed that intentionally spread information and allows the users to tell their friends when they are sharing a fake story.

“When you connect This Is Fake to your Facebook account you can also flag fabricated stories for our moderators,” Slate announced in a statement.

According to Slate, once you install the extension, as you scroll through your Facebook feed, stories that Slate has identified as fake news will be flagged with a red banner over the preview image, indicating that they’ve been debunked.

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via Jean-Etienne Minh-Duy Poirrier. Second image courtesy of The Washington Post.