Following the 2016 election, over 350 newspapers published editorials to speak out against President Donald Trump’s criticism of the media and to call attention to the importance of a free press.

Gene Policinski, president and chief operating officer of the Freedom Forum Institute, as well as a veteran journalist and founding editor of USA Today, supported these actions. A true democracy requires debate, he said, and editorials have a place in that discussion.

However, as the media changes and audiences are confronted with a proliferation of opinions online, the value and presentation of editorials is changing.

How were traditional editorials presented?

Newspapers didn’t always have editorial sections. The first newspapers date back to ancient Rome, when announcements etched on rock were set out for public viewing. Their purpose was to list events in politics and society. Personal commentary came later.

Modern editorials began when Horace Greeley, who founded The New York Tribune, established the editorial page during his tenure from 1841 to 1872 in order to separate facts from personal views.

Since then, they have had a major impact on society. The most reprinted newspaper editorial was written in 1897 by Francis Pharcellus Church, editor of The Sun in New York, in response to a letter from an inquisitive eight-year-old named Virginia O’Hanlon that read: “Dear Editor: I am 8 years old. Some of my little friends say there is no Santa Claus. Papa says, ‘If you see it in The Sun it’s so.’ Please tell me the truth; is there a Santa Claus?”

Church famously replied: “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. […] The most real things in the world are those that neither children nor men can see.” The editorial touched a chord with audiences and made an impact for years to come.

What is changing in the digital era?

The emergence of digital media changed the number of opinions that we encounter and how we view them. The Washington Post's editorial page editor, Fred Hiatt, says 10 years ago, many thought editorials would not thrive in this new media landscape. “Our editorials try to be reasoned and civil, whereas the internet supposedly welcomes loud voices.”

To compete, Hiatt designed an editorial strategy for the digital era. Editorials are listed online under the opinions section along with different styles of commentary. To make the divisions obvious to readers, the section is clearly separated into local opinions, global opinions, letters to the editor and more. Though it is comprehensive — cartoons along with commentary on politics and culture — it is well organized so readers don’t get lost.

“Online, we label our editorials ‘The Post’s View,’ because we found that not all readers understood the distinction we make between ‘editorial’ and ‘op-ed,’” he says. “We have found that the audience for them online is bigger than ever and continues to grow.”

Hiatt stressed that one thing remains the same as in print: “[Opinions are] totally and utterly separate from the news side,” he says. The website makes this clear, too, stating “News reporters and editors never contribute to editorial board discussions, and editorial board members don’t have any role in news coverage.”

However, Dr. Connie Moon Sehat, research community lead at Credibility Coalition, notes that “layout decisions — such as which stories make it to the front page [...] — don't translate when the reader is encountering an article ‘sideways’ from his or her social media feed or through a collection of ‘sponsored content’ on a webpage.”

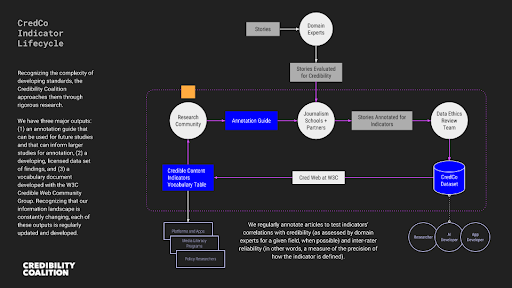

To inform new user experience designs, the coalition is developing credibility standards to highlight and promote factual content. To establish these standards, they work collaboratively with journalism schools and other partners to evaluate the credibility of news stories using an annotation guide developed by their research community.

What are possible solutions for the digital age?

With a proliferation of opinions online, does the internet still need skilled editors — such as Hiatt of The Washington Post or James Bennet of The New York Times — to curate public expression to a digital editorial page?

Although the digital editorial section — The Post’s View — still exists, the publication also launched PostEverything, which represents a move away from the traditional editorial style. This forum takes the conversation outside the newsroom by inviting experts, not just reporters, to weigh in. The goal is to challenge its readers to take in a breadth of sources.

By clearly separating the section from its news content, The Post helps readers identify the source of the information they are receiving, ensuring opinions are not mistaken for fact.

At Credibility Coalition, they discuss who is responsible for distinguishing opinion from news. Is it internet protocols, journalists or media literacy efforts that prepare readers themselves?

With a focus on the latter, Credibility Coalition is studying how well readers separate fact and opinion online. They are also reviewing resources such as the Legit-O-Meter, an online teaching tool that helps the public distinguish reputable news sources from fake news sources and separate opinions and satire. The Legit-O-Meter is geared toward readers ages 10 and up, and it provides materials such as worksheets and lists of suggested news sources in its lessons.

The Legit-O-Meter and other media literacy efforts put the responsibility on the public to separate fact from opinion. However, many people might simply agree with what Virginia O’Hanlon’s father said: “If you see it in The Sun it’s so.”

How can we ensure that debate continues to strengthen democracy while also ensuring that opinions from every loud voice are not taken as fact? When printed words and images seem to inherently possess authority, media organizations must continue to wrestle with this question.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via rawpixel. Second image screenshot of the Washington Post website. Third image courtesy of Credibility Coalition.