Have you ever wondered how well your luggage is treated at the airport? How good the air quality is in your neighborhood? Have you noticed cops speeding past you on the highway and wished you could do more than shake your fist at them? The emerging field of sensor journalism can provide data to help answer all of these questions.

“More of the world is covered in sensors, and journalism is drawing on data more and more for reporting,” said Fergus Pitt, a research fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University in New York City. He studies the principles, ethics and legal issues related to using sensors for reporting.

Journalists can use sensors to create data, Pitt said in a video interview. Sensor journalism is especially useful in developing countries, where sometimes data simply don’t exist.

I interviewed Pitt this spring at Columbia, where I was a graduate student in the School of International and Public Affairs. In the video below, Pitt talks about the role sensors can play in journalism. “No one thinking about this deeply would say, sensor journalism is a field unto itself that should happen devoid of other kinds of reporting, like going and talking to people,” he said. Different journalism fields and practices “should be used together.”

So far, sensors have predominantly been used in investigative reporting and to bring awareness to environmental issues such as air quality and noise. Use of sensors for environmental reporting is still maturing. Sensor journalism brings attention to environmental concerns, but currently doesn't provide the strong quantitative proof needed to advance the field scientifically. As Pitt discusses in the video below, the field is split between high-tech, expensive sensors that provide scientifically valid data and low-budget sensors that shed light on community concerns.

In the video below, Pitt explains how sensors can fill in gaps where there no data exist. “In [some] places you just don’t have any data at all. I think there’s potential for low-cost and potentially, not necessarily the highest-quality sensors, just providing some data. It’s too early to say categorically, but it feels like the possibility is that once some data is produced, there is a demand for more accuracy and more accountability.”

"The biggest question on my mind," Pitt says, is, ‘Can someone like me do this? Someone with less technical skill?’ The answer: yes. Sensor reporting is flexible enough that high-tech people can do it using satellites and drones, but less tech-savvy journalists can figure it out in a few hours using affordable sensors.

How can journalists make sure they are using sensors in a responsible way? In the video below, Pitt discusses the legal and ethical issues that are important to consider when using sensors. Many of the issues are not specific to sensor journalism, he notes. They draw on “existing ethical codes that journalists work under. Get the story right, which just means be accurate.”

Ready to get started in sensor journalism? In an upcoming post, I’ll share a list of projects and resources to check out.

Alyssa Mesich is communications manager at the Segal Family Foundation. She recently graduated with the degree of Master of Public Administration in Development Practice from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University.

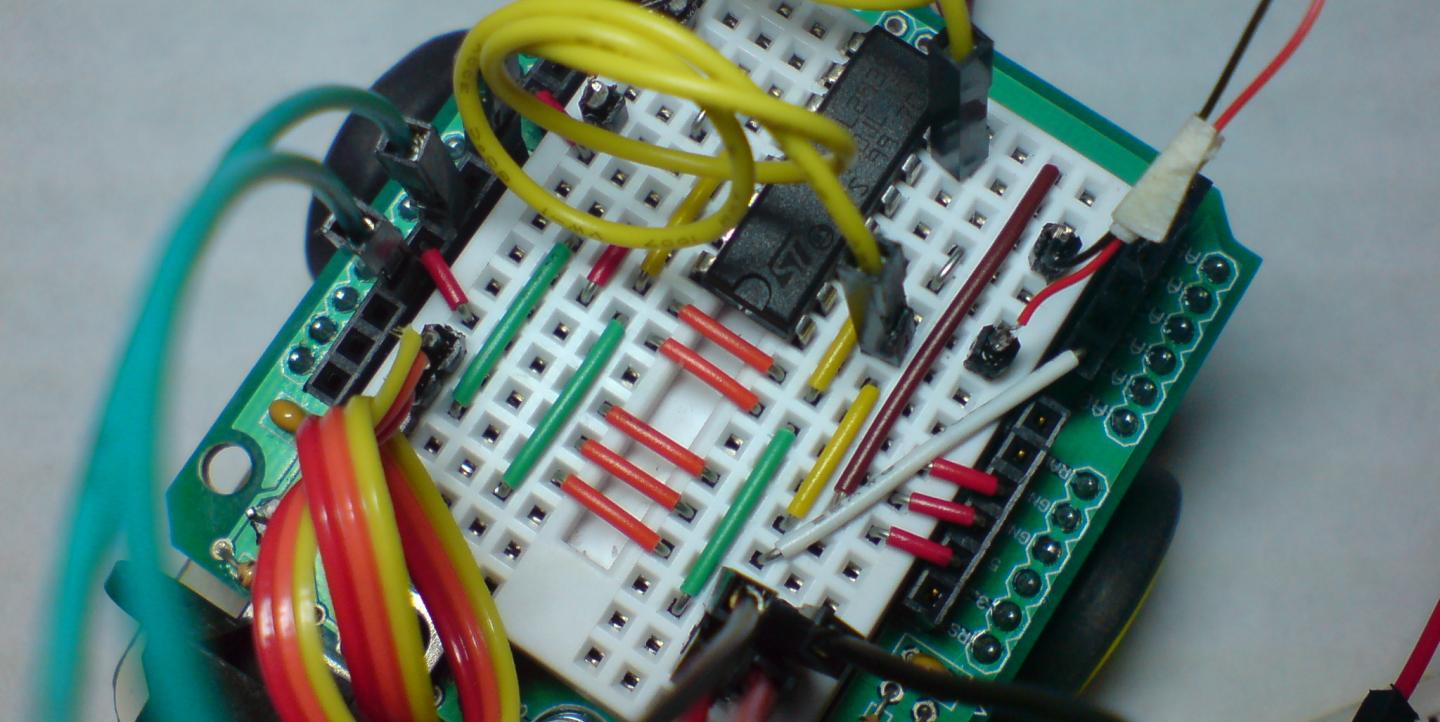

Creative Commons image courtesy of Flickr user m4rlonj.