Speed, accuracy and fairness.

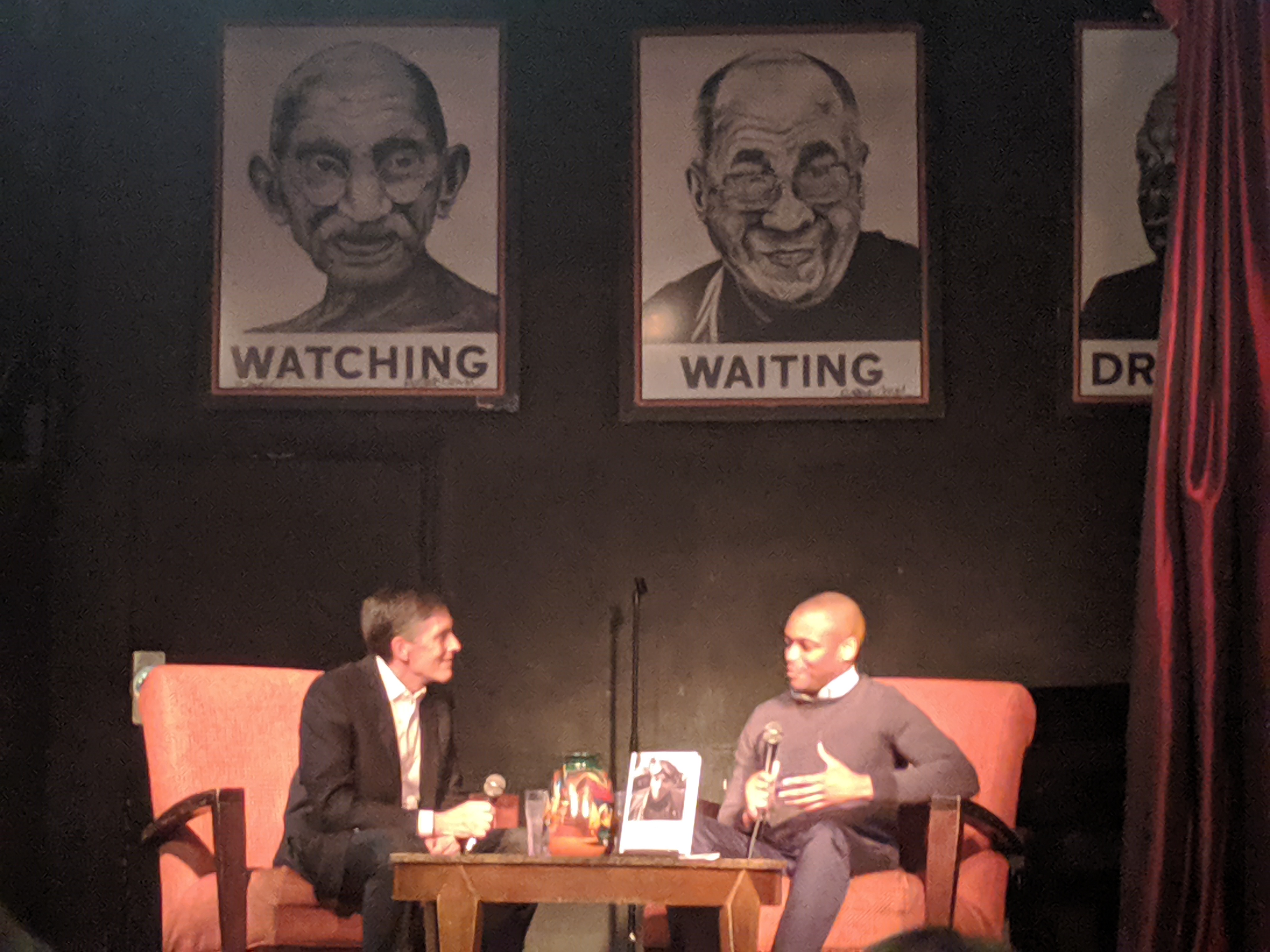

These are journalism’s three core values, according to journalist and author, Peter Copeland, who this month published his latest book, “Finding the News: Adventures of a Young Reporter.”

“Accuracy seems to me to be the minimal requirement for journalism. It’s not just who gets it first, but who gets it right,” Copeland told his audience at a recent book launch event in Washington, D.C.

Copeland boiled his three core values down from 18 lessons he learned over the course of his career, the bulk of which he spent reporting for the Howard Scripps News Service, which today is the E.W. Scripps Company. As journalists compete to master these values, the profession as a whole becomes better, he explained.

“Speed, because I think it is important we have a competitive news environment so that it’s not just one reporter out there covering a story,” he said.

Copeland was based in Mexico City for five years as Scripps’ Latin America correspondent in the 1980s. After, he became their Pentagon correspondent, a position he held through the mid-90s when he assumed editor and manager roles in the newsroom.

“The third value is fairness. That’s the one that’s really the big, broad, difficult one. I went back and forth — is it objectivity, is it telling both sides of a story, or is it balance? What is it that we’re really striving for?” he asked. “I came down on fairness, because even a two-year-old understands what’s fair and what’s not fair, and so you try to be fair to everyone in the story and to the story itself.”

Nearly 40 years after Copeland broke his first story as a young reporter, he looks back on a career that took him to 30 countries across five world regions, all to find — and report — the news.

Copeland spoke with IJNet about “Finding the News,” reflecting on his career in journalism and the state of the profession today. Along the way, he shares advice for reporters just getting their own careers off the ground.

On fairness

It’s easy to identify “fair.” It’s very difficult to apply that to journalism. There’s no story I’ve written that I couldn’t go back and improve and make more fair. So it’s easy to say, but it’s difficult to do in practice. Because you want to be fair to the people you’re talking to, the people you’re writing about, fair to the story overall and then fair mostly to your audience. Are you fairly describing what’s actually happening in the world?

Empathy is a valuable skill to have. If you’ve had a story written about you, you know the feeling. Otherwise, try to imagine it’s you or your family you’re writing about. Sometimes it’ll change your point of view.

On journalists' safety and security

It is more dangerous now, especially in the Middle East where I worked in Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. It was dangerous then, but not like now. I always felt — when I was a reporter — I had a bit of protection by being a journalist because I certainly believed I was neutral, and I didn’t have a side. There was sort of a general sense around the world that that was true, that journalists could go back and forth between the two sides of a war, even in the same day.

When I covered El Salvador in the '80s, I’d go out with the guerrillas that were fighting the government and then come back in the afternoon and go to a press conference with the president, or meet with the army. And you could do that in the same day. Now, there are people who will attack journalists because they’re journalists. Before, I felt if we were injured it was accidentally, that someone was trying to kill the soldier next to me, not trying to hurt me.

The other thing was, I felt some protection being American. Some of this is naive, also, but I felt that we were respected around the world and people knew that we were honest and doing a good job. That was probably not true then either, but that’s what I thought. Now, certainly, there’s less of that. I know reporters who say they’re Canadian because somebody might want to hurt someone who is an American.

On fewer foreign correspondents today

It’s unfortunate for U.S. media organizations that they don’t have their own people covering the world like they used to. On the other hand, the local media or the national media in the countries I used to cover is much better now than when I was there. If you want to know what’s going on in Mexico or Colombia or El Salvador, there are many good local reporters now. Before, when I was there, there were good reporters, but often they were not allowed to publish or write about the things they saw and knew.

On what readers should take away from his book

One, how fun and how great journalism is. We get to travel around, meet new and interesting people, learn new things and then share that with everyone else — and we get paid. I could never get over that.

The other thing is that it’s a meaningful career. It matters. It’s a force for good in the world. I called the book, “Finding the News” for two reasons. One, that’s what we do, we find stories. And two, I found the news as a calling and a purpose in life, and that was deeply satisfying to me.

His advice for early-career journalists

The best advice I have is to go and do it — to just start writing. Even if it’s on your own personal social media page, just start writing and start reporting. Look for part-time jobs, or strings, or a chance to tag along and meet other journalists. Try to insert yourself into the news business and see what happens because, depending on the country, it’s difficult to get a full-time job that pays enough to live. But, if you really love journalism you have to go do it — you can’t wait.

The same goes for if you’re living in one country and you’re fascinated by another country. Don’t wait for someone to send you there. Save your money and go and just block out three months where you’re going to go and explore and try to make connections. Sometimes it works — it doesn’t always work — but if you go and have to come back home after three months, you’ve still learned a great deal and had a good adventure.

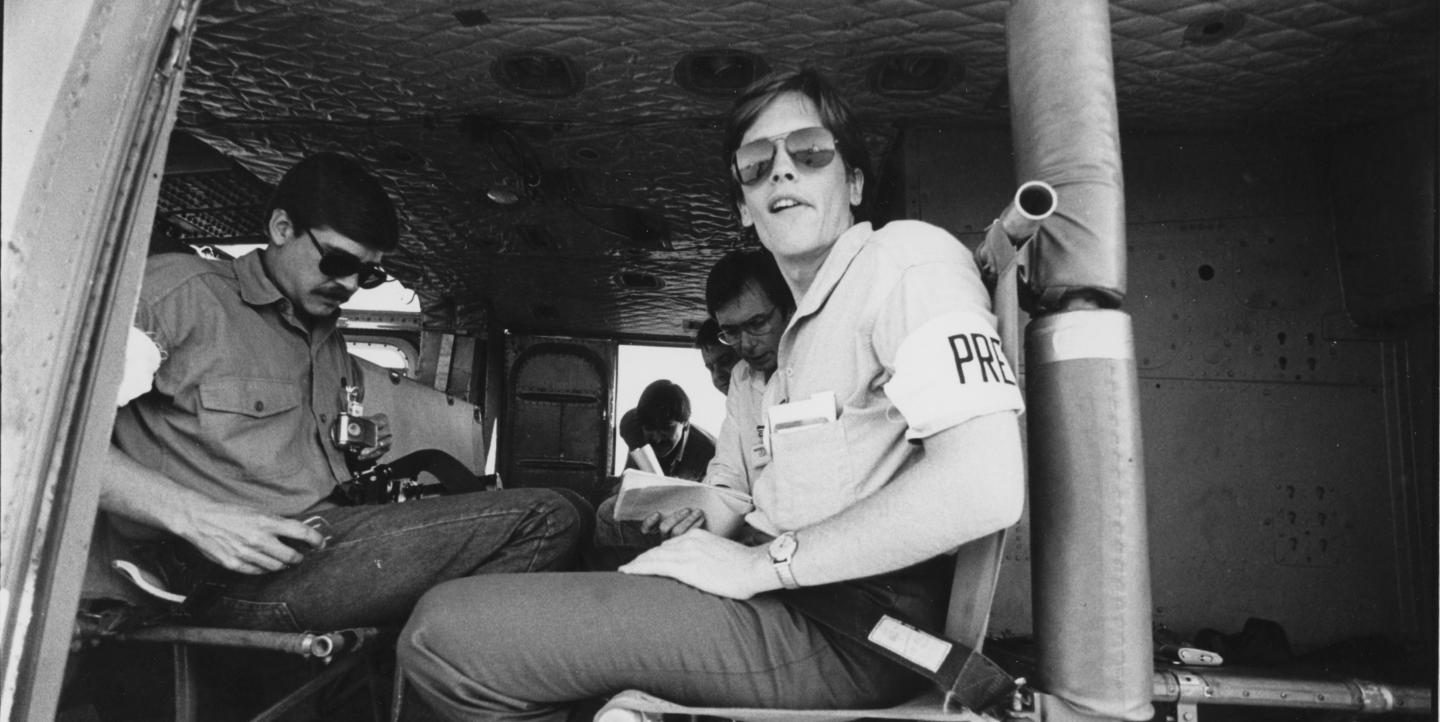

Main photo courtesy of George Hager.