Şaban Vatan, was not convinced when the police records on the death of his 11-year-old daughter, Rabia Naz in Giresun, Turkey, in April 2018 indicated that she committed suicide by jumping from the terrace of her home. Vatan decided to look into the case himself, and he arrived at a different conclusion.

“A black Fiat Doblo hit my daughter, but the hit was not strong enough to result in her death,” he claimed. “Those who hit Rabia Naz then brought her body near my house to make the incident look like my daughter committed suicide." Rejecting the police reports, Vatan argued the driver of the car was the nephew of the province’s former mayor, who is a member of Turkey’s governing party, AKP, and that “the case was covered up” after party representatives pressured investigators.

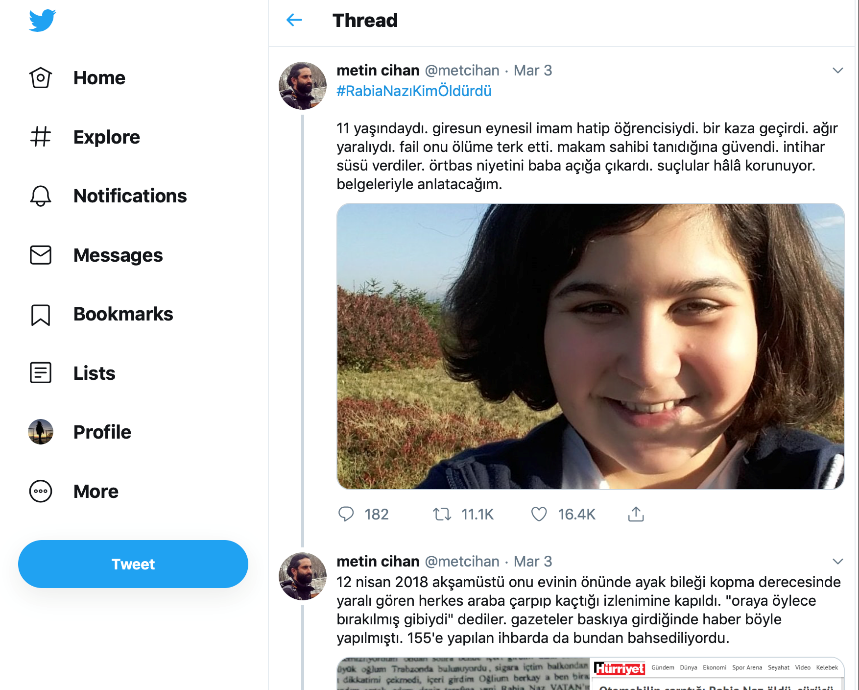

He launched a Twitter campaign to share his findings with members of the mainstream media and politicians. The only response came from Metin Cihan, a citizen journalist. After corresponding with Vatan, Cihan conducted his own investigation and came to the same conclusion: that the incident was not a suicide, but conveyed the signs of a fatal traffic accident.

Cihan brought the case to the public’s attention by enlisting the help of several professional journalists working in both alternative and mainstream media. Together, they created enough public outcry that officials were forced to re-open the case and launch a new investigation.

This type of collaboration between citizen and professional journalists illustrates one way to address the crisis into which the news industry has been thrown by recent technological and political developments — especially in countries like Turkey, where the fourth estate enjoys little independence.

The crisis of professional journalism in the world and in Turkey

The editorial independence of journalists has been weakening, and confidence in media has deteriorated around the world in recent years. Viewers and readers think that the media’s current structure keeps it from fulfilling the promise of objective — unbiased, truthful and factual — coverage, representing a range of views. The increase of misinformation has put mainstream media in jeopardy. Big technology companies have put enormous pressure on journalism by diverting advertising revenues to social media platforms. Those platforms are gradually becoming the primary sources of information and news flow as millions of citizens supply content to one another other through their own accounts.

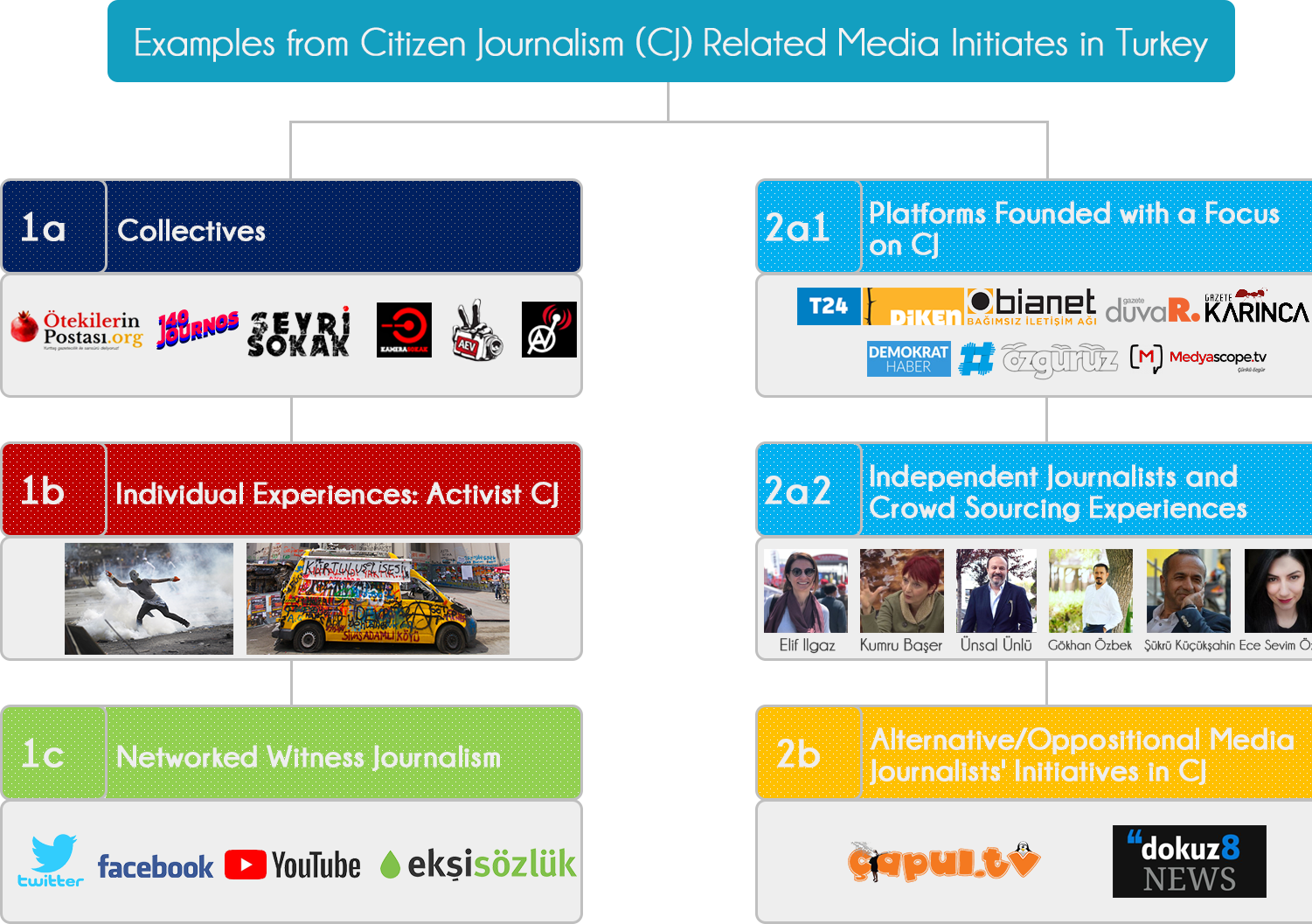

The crisis of professional journalism is even deeper in semi-democratic countries like Turkey, which suffer from new mechanisms of state surveillance, information regulation, and censorship, as well as threat of arrest — which encourages pervasive and insidious self-censorship. In this environment, the most liberal, autonomous and creative forms of journalism are small-scale, independent, collaborative initiatives in the alternative or oppositional media habitat.

Today, many professional journalists in Turkey who were forced out of mainstream media organizations can work only as part of these new initiatives, where they build solidarity and cooperation with citizens and alternative media. Some still make an effort to write as individual journalists using their personal accounts on social media. Others have established "hybrid" platforms where professionals meet with citizen journalists from different networks of civil society to work together. These new platforms, which are still very small and unorganized in structure, aim to empower society and defend basic rights and liberties — such as free expression and access to information — that the country’s compliant mainstream media fail to safeguard.

Media survey in Turkey

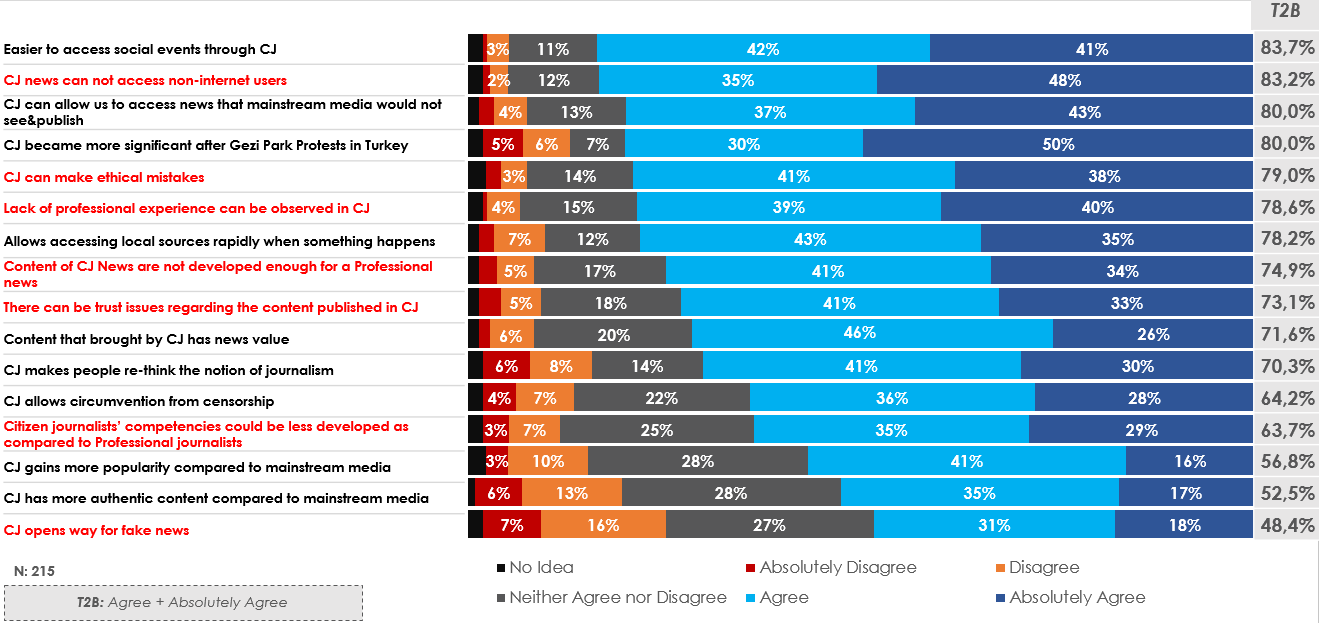

The organization I work for, MEDAR (Media Research Association), recently conducted a survey based on interviews with 306 professional journalists in Turkey to understand the potential areas of cooperation between professional and citizen journalists. Professional journalists in this study were asked to describe their perception of citizen journalists and their work.

These are our key findings:

-

Mainstream media outlets do not generally adhere to journalistic ideals and ethics. Rather, they curate “news” to support the arguments and policies of the current regime. Journalists working there cannot practice their profession freely. Objective, rights-focused, unbiased journalism is relegated to alternative and oppositional media platforms.

-

The number of small-scale, alternative and oppositional media platforms is large — and growing, largely because of the negative developments in the mainstream media.

-

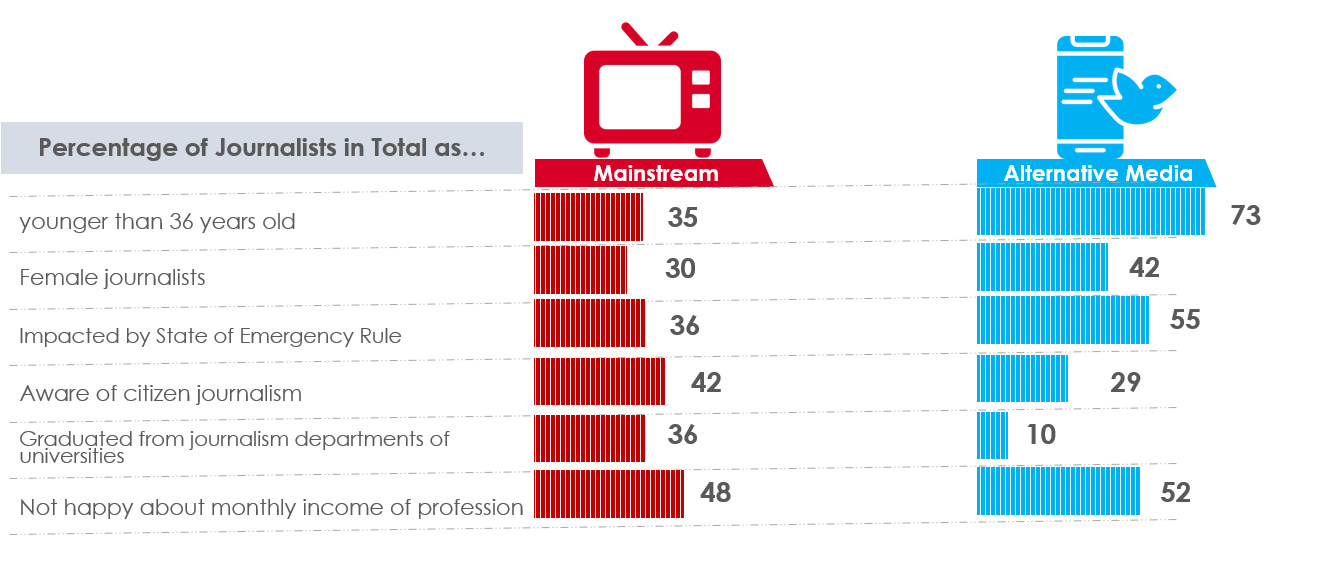

There is a clear differentiation between the profile and attitudes of journalists working in mainstream media and those working for independent news portals and oppositional media. The latter are disproportionately young and female, are more active users of social media, are more inclined to follow global publications closely, and are more socially conscious, exhibiting a high level of interest in rights- and gender-related topics.

-

Such platforms represent the only viable alternative to Turkey’s monolithic mainstream media, and the only hope, at present, for pluralistic representation in the public sphere.

Is citizen journalism an option?

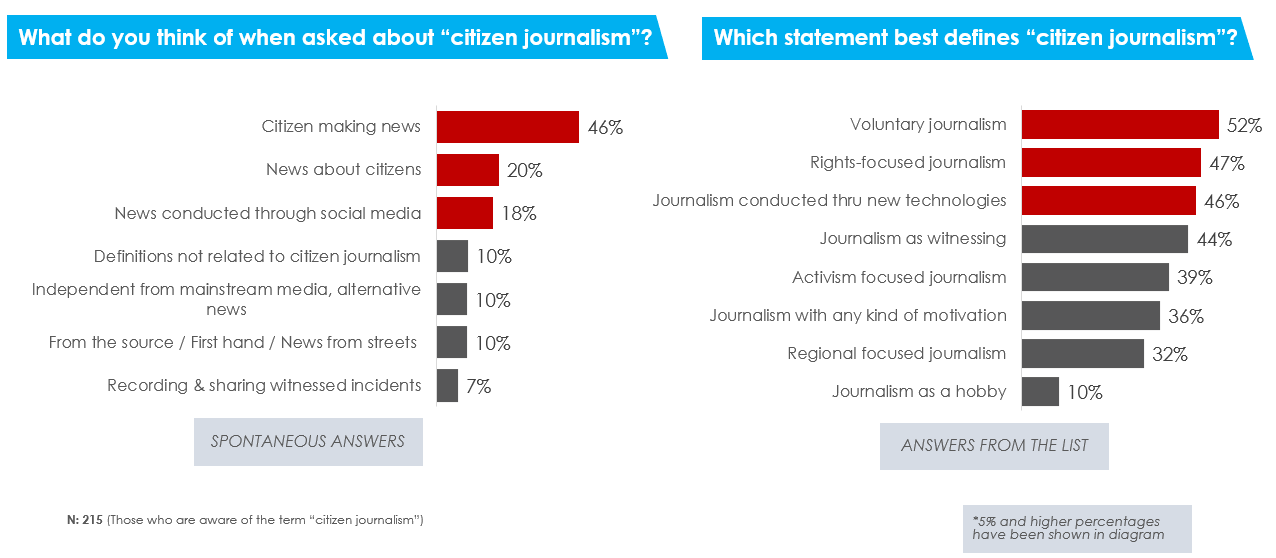

Professional journalists were asked to describe what they understand by “citizen journalism.” Their initial answers tended to define citizen journalism as “citizens making news,” emphasizing the word “citizen” in the sense of “non-journalist.” They also tended to think of it in terms of doing “news in citizens’ interest.” The role of social media was also mentioned. For example, one respondent said, “Citizen journalism is news that is made through social media.”

Their responses to follow-up questions changed drastically. They then spoke about citizen journalism more in terms of it being voluntary, eyewitness reportage with a focus on rights and activism and enabled by new technologies.

When asked to evaluate the different aspects of citizen journalism, professional journalists tended to emphasize its potential, particularly as a way for citizens to access information about civil society initiatives that the mainstream media ignores. However, they also cautioned against its risk to professional journalistic codes. Many regarded citizen journalists as inexperienced and lacking in journalistic skills, and argued that their content is still in a raw state that requires further polishing before it is ready for publication. Half of the journalists surveyed expressed concern that if citizen journalism becomes more widely established and accepted, it could facilitate the spread of disinformation.

What happened to Rabia Naz is still unknown. But thanks to the collaboration of a citizen and professional journalists, the Turkish public now knows about her case and officials’ attempt to cover it up. Their efforts likely contributed to AKP’s loss in the municipal elections of March 2019. And with the public now interested, her father says he will follow it up until the perpetrators are found.

Yunus Erduran is the Research Director of MEDAR (Media Research Association) in Turkey. He is also the founder of a citizen journalism network in Turkey, and has contributed articles to many media outlets, and co-authored three books in Turkish.

MEDAR's research was conducted with support from The Guardian Foundation and the Social Sciences Association in Norway, Samfunnsviterne in Turkey, 2018.

Main image CC-licensed by Unsplash via Pablo Heimplatz. All other images courtesy of the author.