In Pakistan, reporting on victims of terrorism is a priority. But during a recent journalism workshop in Lahore, one editor raised an important question: With attacks being so common, how do we get people to care?

In December, Dawn.com, the online version of the Pakistani newspaper, launched a groundbreaking project that addresses that very concern.

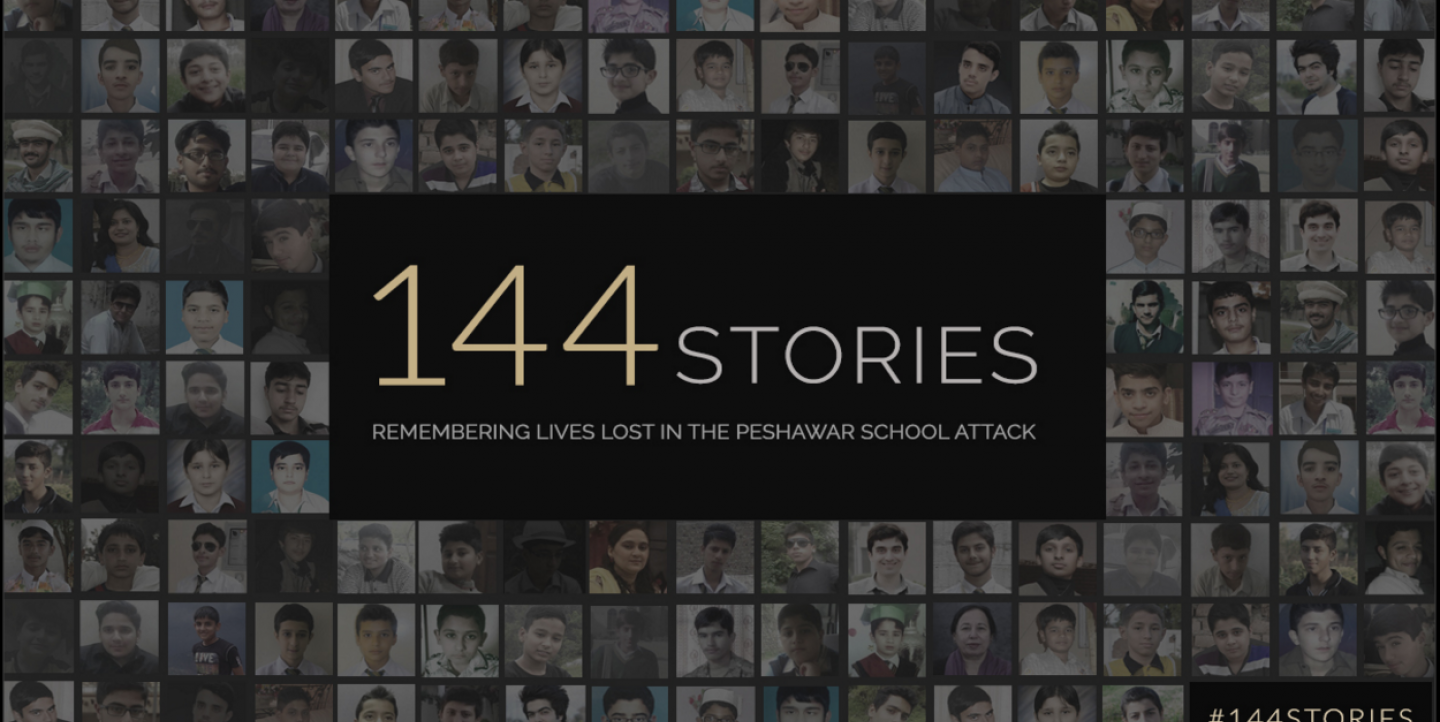

The project, titled 144 Stories, serves as a virtual memorial to the lives lost on Dec. 16, 2014, when Taliban gunmen attacked a public school in Peshawar. When the rampage ended, 144 were dead — most of them schoolchildren. News reports called it the deadliest Taliban attack in Pakistan’s history.

I clicked on the link and was immediately transfixed. The sweet, innocent faces of children filled the computer screen. 144 Stories provides vignettes capturing some aspect of each child’s life —what made them happy? What did they aspire to be? What dreams did they hold?

“We wanted to look past the death toll and put faces to the story,” wrote Atika Rehman, lead editor for the six-month initiative. “Our reporters worked tirelessly to reach out to the relatives and teachers of the 144 students and staff members who were killed. They collected photos and anecdotes to document lives cut mercilessly short.”

During the reporting process, “We wept and prayed,” Rehman wrote. “And we vowed never to forget.”

In an email exchange, Rehman described how Dawn’s editors organized and managed the project. Among her key points:

Form a team and delegate

Rehman tapped a chief reporter in Peshawar to compile a list of the victims’ names and addresses. She assigned specific reporters to interview families and obtain photographs. As copy came in, an editing team organized the data according to ages of those killed.

Set limits early in the process

To ensure continuity, editors created a template for the profiles and set word count limits so readers would get close to the same amount of information about each victim. All team members were aware of these goals and limitations.

Bring developers and designers on board early

Graphic designers worked on the look of the page, including background color and slide show placement. Developers wrote the code to include special elements in the stories. For this project, a free online tool – Google Slides – was used to match photos with quotes to illustrate the tragedy.

Track progress and promote collaboration

Rehman kept tabs on how many profiles each reporter filed per month. If copy was delayed because they were working on breaking stories, she reached out to discuss how they could restart the process and meet the deadline.

The reporting for 144 Stories is stellar and, at times, heartbreaking. Readers learn about eighth-grader Uzair Ali, who saw the attackers and leapt to shield his friends by lying on top of them. He was shot 13 times and killed, but he managed to save his companions.

14-year-old Fahad Hussain opened a door so his friends could run out. He stayed behind to make sure everyone was evacuated. The killers gunned him down.

First-grader Khaula Bibi was the youngest victim and the only female. The 6-year-old was killed on her very first day of school. Relatives noted that even at her young age, Khaula championed the right of girls to be educated.

Rehman describes public reaction to the project as “astounding.” Some told how they wept as they came to know each victim.

“[This project is] something that reminds us of the dark days we’ve been through,” one reader wrote. “Telling us how brutal our enemy is ... and urging us to eliminate them once and for all to maintain peace in the country.”

Rehman said many readers told her that 144 Stories made them believe in journalism again.

“To me, that is a huge victory in a country where journalists are looked at with distrust,” wrote Rehman.

Main image is a screenshot of 144 Stories' home page.

Secondary image of Atika Rehman provided by Rehman.