Claims that ineligible persons will be allowed to vote are one of the most common types of disinformation that circulates around elections.

Bad actors may falsely allege that deceased persons are included in voter rolls, or that people will use the IDs of deceased persons to vote, in attempts to defraud the election.

In some cases, deceased persons may appear on voter rolls due to errors in registration; authorities are usually able to correct these errors. In other cases, individuals may pass away between the time the voter rolls are created and the election date. Countries’ electoral systems typically include methods to address this problem, as well.

For example, during the 2022 general elections in Costa Rica, the government permitted voters to use expired identity cards at the polls due to the pandemic. Disinformation claimed that this would allow thousands of deceased people to vote. To the contrary, the electoral roll was in fact updated up until the day of the election to remove the names of those who had passed away.

Another example occurred in Peru, where a video circulated during the country’s 2021 elections which showed an electoral act that was supposedly signed by a deceased person. This was a typing error, however: the user had simply entered the last digit of the identity card incorrectly.

False narratives around ineligible voters typically target marginalized communities, and often use social prejudices. This happens in a variety of contexts, and elections, when tensions are high, are no exception.

In many countries, disinformation campaigns also seek to spread fear about immigrants voting illegally. In countries where foreign nationals are legally allowed to vote, disinformation claims may put forth that those who do not fulfill the legal requirements will still be allowed to vote.

During the 2022 U.S. midterm elections, false claims about undocumented or newly arrived immigrants voting illegally circulated widely. These assertions ran contrary to the reality that for immigrants to be eligible to vote in the U.S., one must be a citizen, over 18 years old, and have completed a naturalization process that can take years. A clear example of this disinformation narrative occurred in the U.S. state of Colorado, where bad actors falsely promoted that the state government had sent 30,000 ballots to undocumented immigrants.

Elsewhere, in Colombia, false posts circulated that claimed Venezuelans could vote in elections. However, according to Colombian regulations, foreigners can only vote if they have a visa, foreign ID card, and have been residents in Colombia for more than five years. They also only have the right to participate in municipal or district elections — not presidential elections.

In Chile, similar disinformation spread, claiming that foreign residents who had arrived in the country less than a month before could vote in the national plebiscite for a new constitution. This was again false: only foreign residents who have been living in Chile for more than five years can vote.

It is extremely important to be careful when covering elections and related topics. Make sure to provide accurate information and avoid falling into discriminatory discourse or creating panic among voters.

During any electoral process, errors may occur. It is crucial not to simply take these cases at face value, and present the irregularities as evidence that unqualified individuals will vote in widespread numbers.

Coverage of such incidents should instead aim to confirm whether the State has implemented mechanisms to address any flaws in the electoral system. It is also necessary to determine whether such incidents are isolated or the result of an organized attempt to interfere with the election process.

Failure to do so could result in the spread of disinformation that seeks to delegitimize the electoral process.

This resource is part of a toolkit on elections reporting and how to spot mis- and disinformation, produced by IJNet in partnership with Chequeado and Factchequeado, and supported by WhatsApp.

For more information on electoral disinformation, visit PortalCheck.

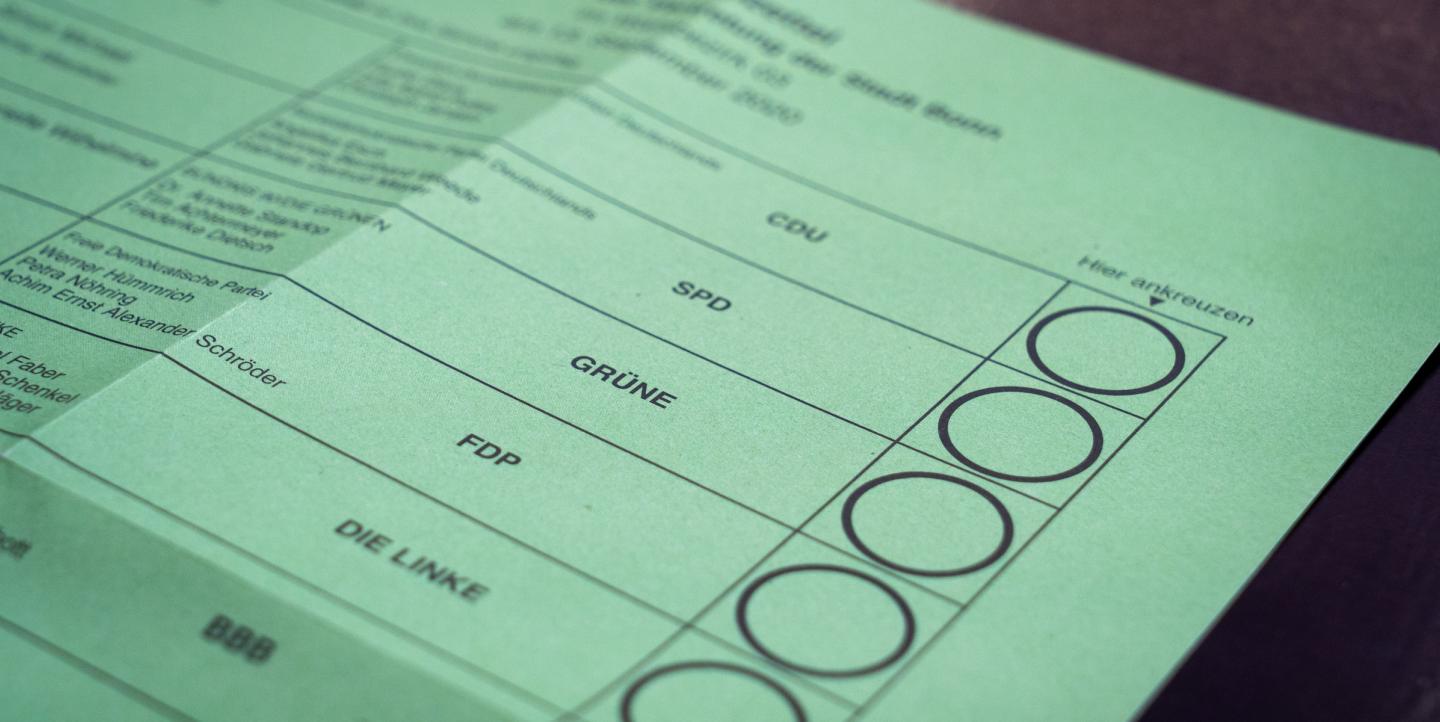

Imagen by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash.