The emergence of fake news in the lead up to the August 8, 2017 elections was unprecedented. Kenyans were inundated with fake news, inaccurate polls and misleading ads. This proliferation is not unique to Kenya, but the jury is still out on whether the sophisticated ad campaigns adopted by the ruling Jubilee Alliance in Kenya had any impact on the outcome. What is clear is that it was and remains imperative to counter the narratives of fake news.

In the period leading up to the August 2017 presidential election, a study by Portland Communications showed that nine out of 10 Kenyans had encountered fake news. This rise is driven in part by the proliferation of so-called ‘dark social’ networks, where messaging apps like WhatsApp and Telegram are used to spread misinformation.

The petition challenging the outcome of the August 8 election led to a surge in fake news and propaganda against the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) and its commissioners. The stories then shifted to the Supreme Court judges after they nullified the presidential election and ordered a revote.

Fact-checking tools

The period leading up to the repeat presidential election saw a significant amount of fake news. For example, a fake poll was circulated to media houses claiming that the main candidates, incumbent-President Uhuru Kenyatta and opposition leader Raila Odinga, were neck-and-neck. A popular radio station unwittingly became the purveyor of the fake opinion poll, which had been published on a parody site of an internationally-recognized opinion polling firm, Ipsos Synovate.

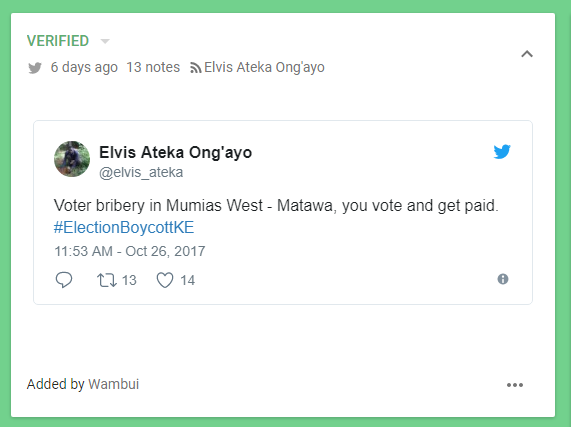

Ahead of the repeat election, Code for Kenya, PesaCheck and the Election Observation Group (ELOG) collaborated to establish a team to verify claims in real time. Using Check, a tool developed by Meedan, the team was able to check claims made on social media and in mainstream media over a 72-hour period beginning October 26, 2017.

Electionland, a ProPublica project, used Check during the US election. This was the first time, however, that the platform was used in a Kenyan election.

Six Daystar University journalism students made up the verification team, which was based at the media monitoring office at ELOG’s Nairobi headquarters. The student volunteers were from a class of 35 who underwent training on verification and fact checking carried out by Code for Kenya lead and ICFJ Knight Fellow Catherine Gicheru and myself. The students learned the basics of fact checking and verification, including how to do a reverse image search to check the veracity of an image; how to identify individuals tweeting using a particular hashtag through Twazzup; and how to find who actually owns a website using Whois.

The six volunteers also learned how to use Check to help verify incident reports and claims coming from ELOG observers and from social media. The verification was done through interviewing individuals on the ground where incidents were being reported and cross-checking with election observers and their networks.

ELOG deployed 2,196 observers in in all parts of the country except 10 counties where security was uncertain. These observers filed hourly incident reports that needed to be quickly and accurately be verified to allow appropriate action from ELOG.

To identify claims to be fact-checked, we adopted a six-step process:

-

What is the claim?

-

Who made the claim?

-

What time was the claim made?

-

Where was the claim published/broadcast?

-

Is the claim true or false?

-

What response is needed?

The terms Verified (if the claim was found to be true), In Progress (if a claim was not immediately verifiable and required further checking) or False (where the claim was found to be an outright lie) were used categorize each assertions. Claims that could not be conclusively checked due to limited evidence were marked as Inconclusive.

From televisions installed in the media monitoring room, we were able to keep track of what was being broadcast and the claims being made. All checks that the team conducted were included in the hourly updates filed by the ELOG’s situation reports and informed the press statements that ELOG issued before, during and after the election.

Staying ahead of the curve

A pattern soon emerged. Reports of disturbances would show up on social media roughly 15 to 45 minutes before they were reported in mainstream media. In essence, the fact checking team was able to stay ‘ahead of the curve’ by monitoring what was happening on social media.

There were also interesting events that the mainstream media and journalists overlooked. For example, in some constituencies of Nyanza, voting peacefully took place, despite the media reporting an election boycott.

The most interesting claim handled was one that said voters in Mumias were being bribed to come out to vote. An ELOG observer in Mumias interviewed scores of residents, who confirmed to the observer that some individuals had indeed been going door to door offering money to voters to come out and vote. Because this is an election offense, ELOG alerted IEBC officials.

In total, the verification team made more than 200 calls to ELOG’s observers, tracked more than 100 claims and found one in five of them to be outright falsehoods. The most obvious falsehoods were the fake memos published using letterheads mimicking the logo and colors of the opposition group National Super Alliance (NASA). One memo purported to be an invitation from Raila Odinga to his presidential swearing-in ceremony at Uhuru Park on October 27.

Cutting out the noise

Fact-checking claims can help in cutting out the noise during a crisis and preventing panic. By countering misinformation with facts, journalists can help combat the menace of fake news and direct audiences to factual and accurate information.

Our experience has shown that there is a need for real-time fact-checking, particularly in tense times like elections. Journalists must look to social media not just as a place to break news but also a way to gather useful information —information that needs to be fact-checked and verified before publication.

Main image CC-licensed by Flickr via Taylor.

Secondary image via PesaCheck.

This story first appeared on PesaCheck and has been condensced and republished with permission.