The International Center for Journalists’ (ICFJ) Disarming Disinformation initiative is a three-year programme, supported by the Scripps Howard Foundation, that aims to slow the spread of disinformation through multiple programmes such as investigative journalism, capacity building and media literacy education. ICFJ partnered with MediaWise from the Poynter Institute to develop and deliver media literacy programming.

The media literacy training of trainers programme accepted global participants for two different cohorts. The participants are community leaders who will educate others on the importance of media literacy and how to apply those skills in real life. The article below is one of five impact stories selected from the second cohort. The programme thus far has trained 27 trainers who have reached more than 3,200 people.

A high school history teacher and fact-checker, Gabriel Narváez, wanted to bridge his two professional worlds. His goal was to strengthen public discourse by teaching his students to question what they read and share online.

Narváez sees hope in the next generation of Ecuadorians. He also sees a challenge. Even the best education can’t compete with the flood of unverified information that shapes young people’s digital lives. He worried his students didn’t care whether what they saw on social media was true. But he found something unexpected: his students were already skeptical.

When Narváez heard of the Disarming Disinformation initiative — a collaboration between Poynter Institute’s MediaWise and the International Center for Journalists — he saw a way to sharpen that skepticism into skill.

The workshops

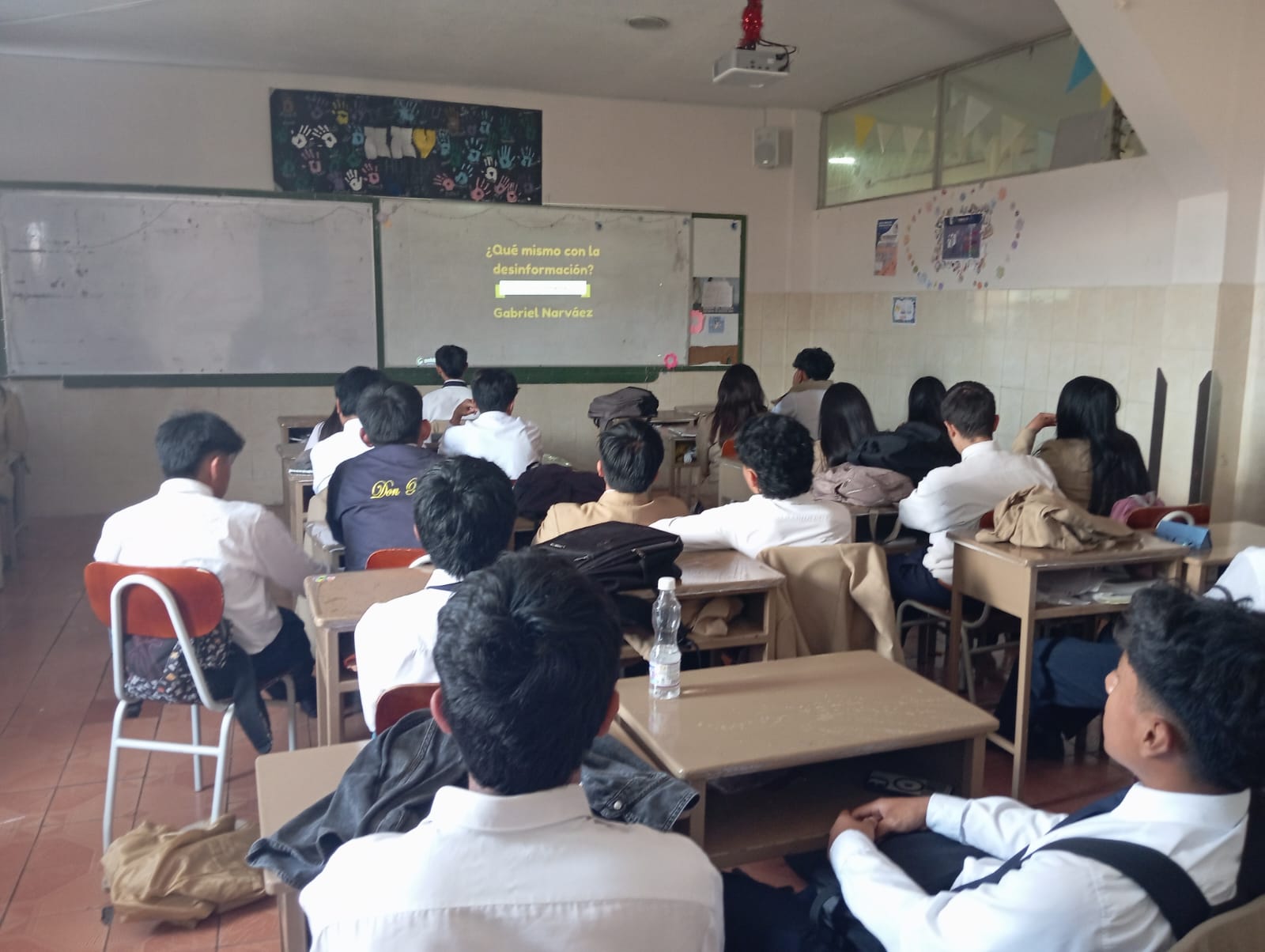

As a high school teacher, Narváez had a built-in audience: his students. He wants to equip them for their present and their future. Narváez worked with his school’s administrators to design a workshop that ultimately reached 134 high school seniors. He integrated some lessons into his regular classes to build a baseline that he could draw on in his workshops.

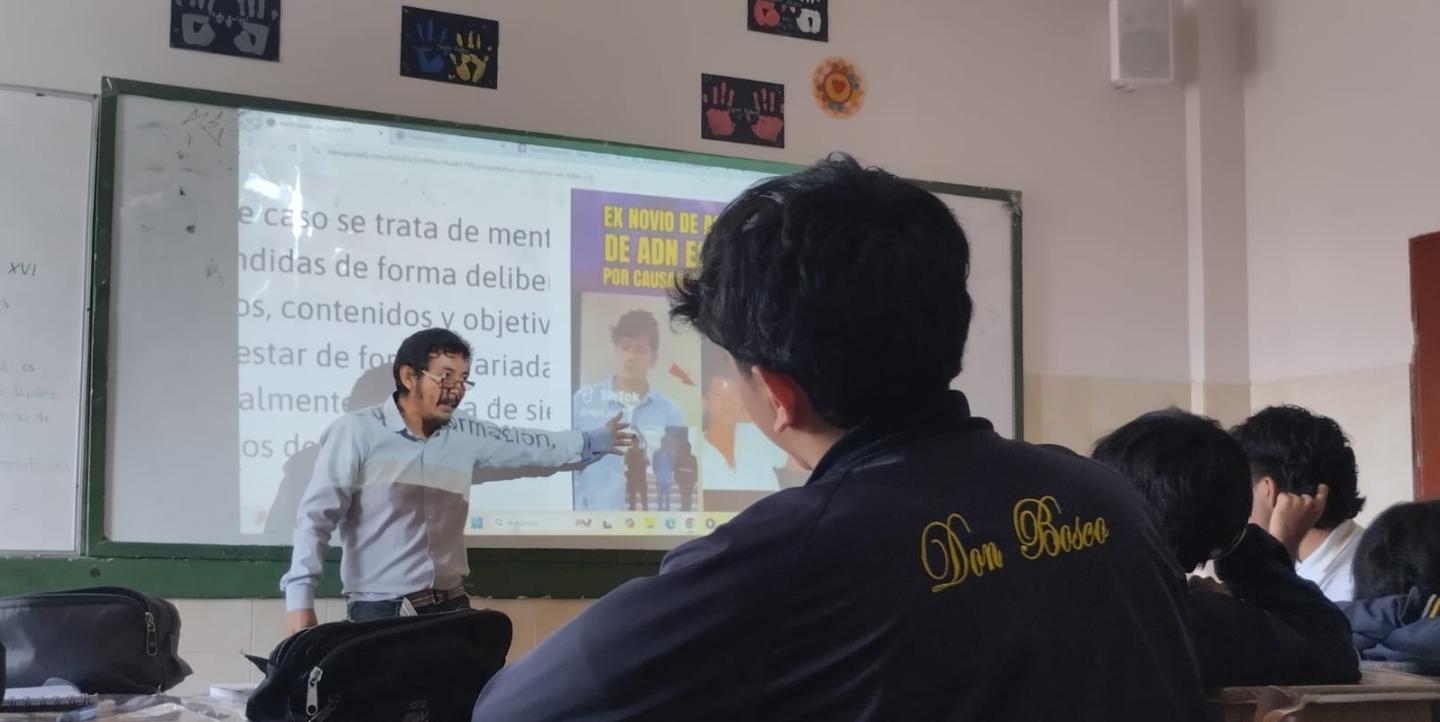

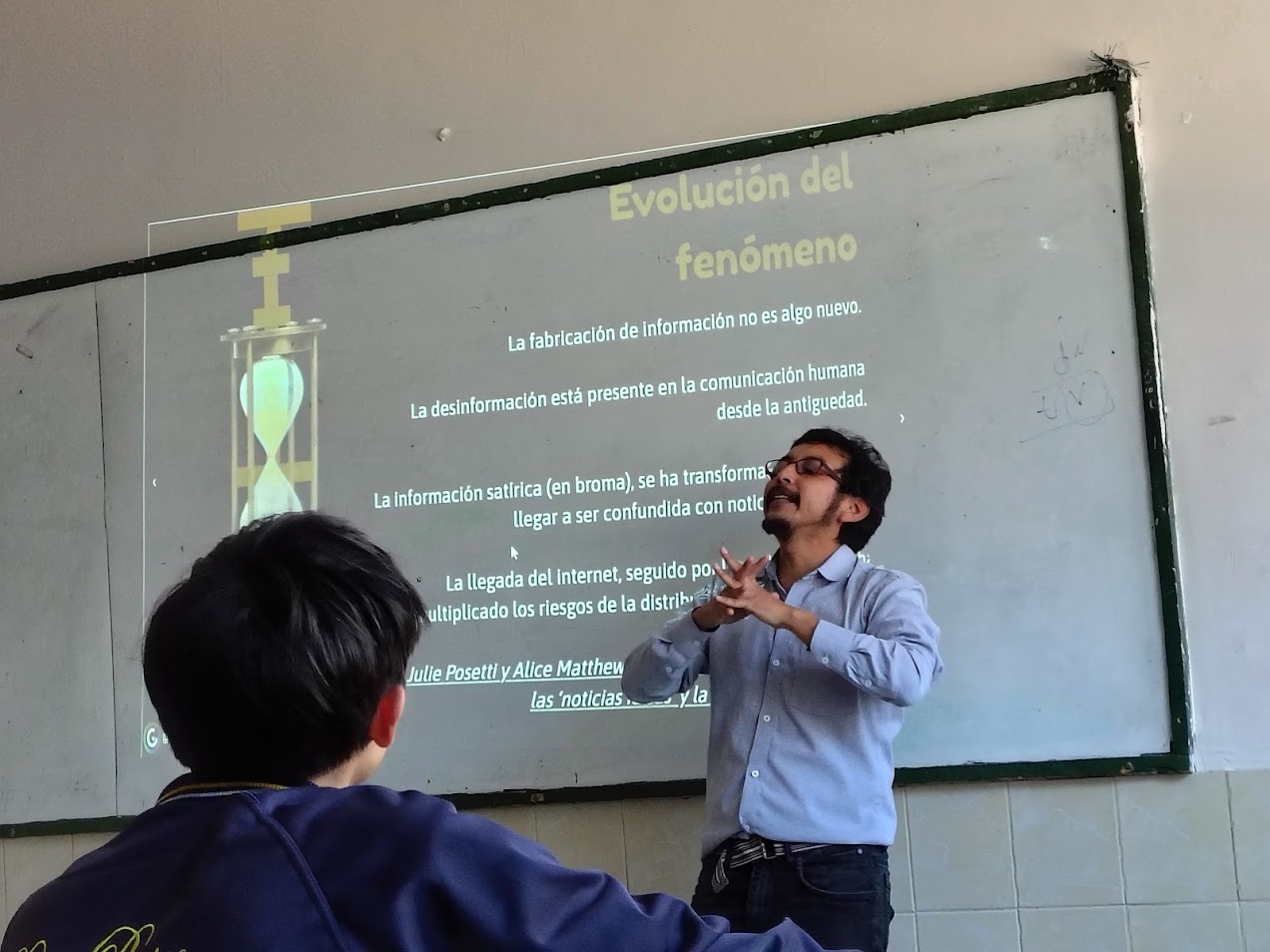

He began by tracing disinformation throughout human history. Then, he brought the lesson into the present, explaining the difference between misinformation (unintentional falsehoods), disinformation (intentional falsehoods), and malinformation (the deliberate use of private truths to cause harm).

With this foundational knowledge, Narváez introduced hands-on verification tools: Google Lens, FotoForensics, TinEye — and guided students through hands-on exercises. The tools fascinated them. Some jokes about using them to find out if their classmates’ photos had been edited. The humour underscored a deeper realisation: These tools could be helpful if someone is a victim of image manipulation.

Impact

Narváez incorrectly assumed teens do not know how to search for verified information online. He realised that many have a variety of tools and skills, to an extent, capable of discerning if information is true or false. His workshops amplified their understanding. But he also discovered that whether they use such skills depends on their interest. They are more likely to apply their evaluative skills for a rumour involving a soccer player or a celebrity, but show little interest when it is related to a politician.

During their final exams, the students were asked what they considered the most valuable lessons learned during high school. Their answer? Overwhelmingly, they said Narváez’s media literacy workshops equipped them with concepts and knowledge to navigate not only their social media feeds, but their world.

Reflection

Today’s teenagers are digital natives. They were born into a world of digital connectivity and instant gratification, and artificial intelligence is a growing component of that world. They perceive the world differently than those who grew up at a time when cellphones, social media and the ability to easily generate deepfakes did not exist.

Narváez found that many of his students approach online content starting from a standpoint of permanent doubt. In class, they were able to apply their knowledge to identify small, false details in headlines and images.

“We should start with a culture that fosters proactive methodical doubt,” Narváez said. “We must understand that the information we consume is influenced by a series of viewpoints and details that are not visible in the content we receive as such. Therefore, our obligation is to investigate, search and immerse ourselves in a plurality of voices that brings us closer to a criterion rich in verifiable data.”

What’s next

Colleagues at other schools saw Narváez’s success and the impact his workshops had on the students. They hoped to implement it in their own institutions. However, due to bureaucratic and logistical obstacles, several were unable to do so. Others were.

Narváez’s goal is to make media literacy workshops a standard part of the Ecuadorian curriculum. He continues to work towards that effort.

Through media literacy, he wants to empower teens to think critically and broadly about their world and the fight against disinformation.

Main image courtesy of Victoria Lara.

Renata Salvini contributed to this article.