Now that we know that Dropbox snoops in our files and that Google shares our data with the NSA and the FBI, journalists must acquire new skills to avoid leaving a trace behind or let others track anonymous sources.

Data on our data is called "metadata." It's there every time we leave an electronic record behind. When we take a photo, it will have data about the camera, the time it was taken, and probably the name of who took it if geolocation and face detection are enabled on the device. So taking a picture now is much more than just a photo. It's telling information about yourself.

During this year's Media Party, organized by Hacks/Hackers Buenos Aires, Daniel Foguelman from the security company InfoByte, led a workshop on discovering and cleaning your metadata. During the workshop, Foguelman taught journalists how to discover and remove information from pdfs, jpgs and htmls, to avoid leaving information behind unintentionally.

Every time we send documents, in addition to sending the content in the document, we are sending information about the machine that processed it and the operating system. If the software is registered, surely you will find your name in the properties window. When we send an email, we are not just sending our content and recipient. Collectively, we also reveal patterns in how we interacting with society and one another.

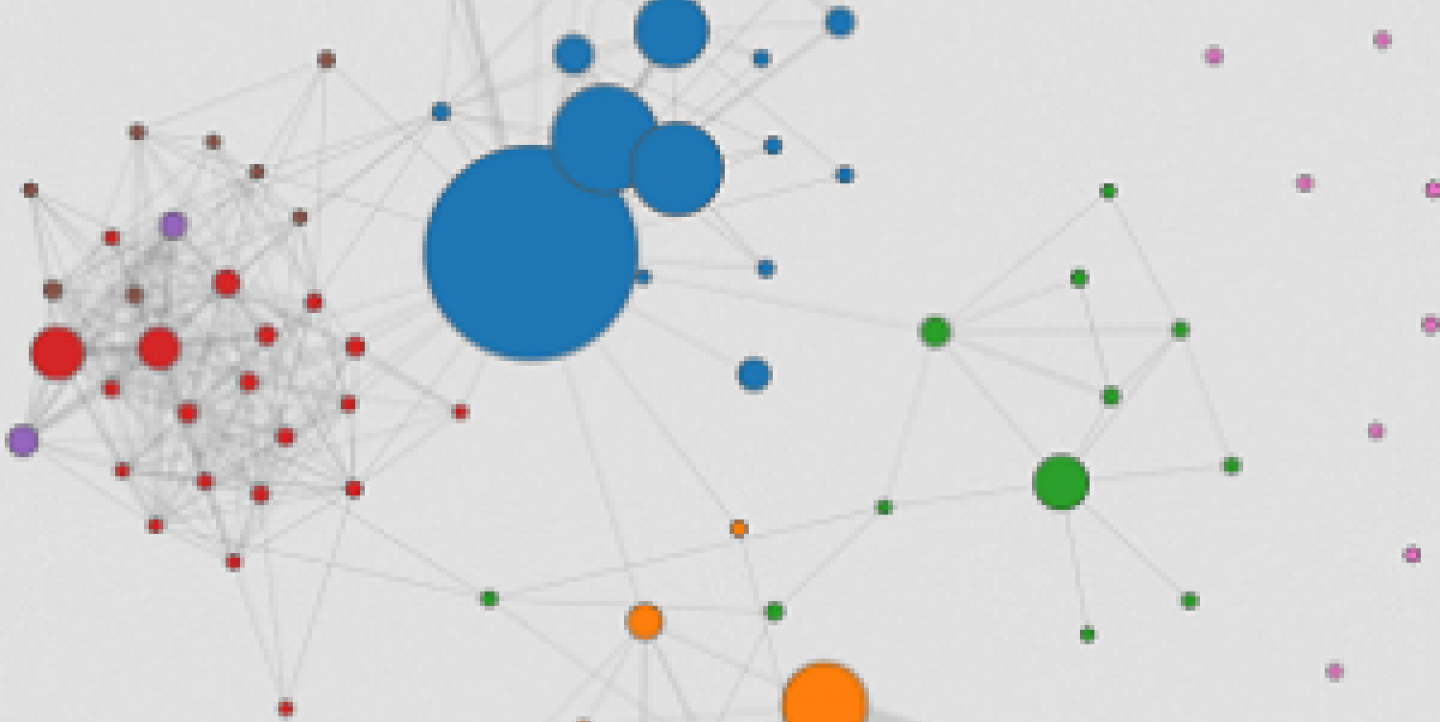

Some of this was uncovered by the Immersion experiment at MIT, which visualized content from Gmail accounts in order to find communication patterns and behavior.

MIT researchers were inspired by the case of Edward Snowden, who showed us the importance of metadata tracking by U.S. intelligence. Basically, as it has been written many times, when communicating by Gmail - which has access to such data – you can quickly learn about users' groups, relations, friends, contacts; in short, everything that is inferred from the behavior of our data.

At the Knight-MIT Civic Media Conference, in late June, at the entrance of the Media Lab, there was one giant screen showing data of those who had dared to simply share their usernames and passwords for the purpose of the demonstration, which showed how a machine can quickly deduce relationships.

Journalists' documents produce metadata, and all that data, which isn’t in the content, leave clues. Court documents have metadata: the court number, name of the judge, the title and number of pages. But we cannot live without metadata. We cannot send an email without knowing where it will go or take a picture without knowing which camera shot it. We cannot talk on mobile phone without the system knowing where we are.

Metadata, of course, can also be a source of information for investigative journalism: a way to get the anonymous message, a way of connecting trails. At MIT, during a hackathon organized by Knight-Mozilla Open News, Waldo Jaquit of State Decoded and Chase Davis of the New York Times led a project called Judgmental.

The idea was to analyze legal texts that were in PDF format, automatically find the metadata, create an API and query the documents interactively. Hackathon attendees built the prototype in two days. They figured out a way to find state documents with metadata that could be used by legal researchers, based on finding the documents' marks.

Removing so much metadata when addressing a journalistic investigation is a difficult and cumbersome task. The best way to do it is to investigate oneself.

So start looking at what you're leaving behind. Search your name on Google; look at the "info" section when you're writing or editing documents; try to understand how other people are watching your data; open your images on different computers and try to understand what they're telling others about you.

Knight International Journalism Fellow Mariano Blejman is an editor and media entrepreneur specializing in data-driven journalism.

This post was translated from Spanish to English by Andrea Arzaba and Maite Fernández.

Global media innovation content related to the projects and partners of the ICFJ Knight International Journalism Fellows on IJNet is supported by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and edited by Jennifer Dorroh.

Image: Screen grab of Immersion.