Social media platforms have teemed with misinformation around the Russian invasion of Ukraine over the past month. Due to the large amounts of false content online, distinguishing between reliable and inaccurate information has been a challenge.

What follows is a set of guidelines and tools to help journalists report on the developments in Ukraine without falling victim to misinformation.

Manipulated video content

A few hours after Russia announced the launch of its military operation in Ukraine on February 24, a video said to be of Russian jets entering Ukrainian airspace went viral on social media, garnering hundreds of shares and thousands of comments on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. It turned out, however, to be a clip from a five-minute video of fighter jets first posted online years ago.

This case is not unique, unfortunately. Other videos have circulated widely on social media despite being outdated, or from unrelated locations. In these instances, specialists recommend using Verification Plugin, a tool that allows journalists to fragment videos into keyframes — under the ‘Keyframes’ tab — These can then be used to run a reverse image search through several search engines.

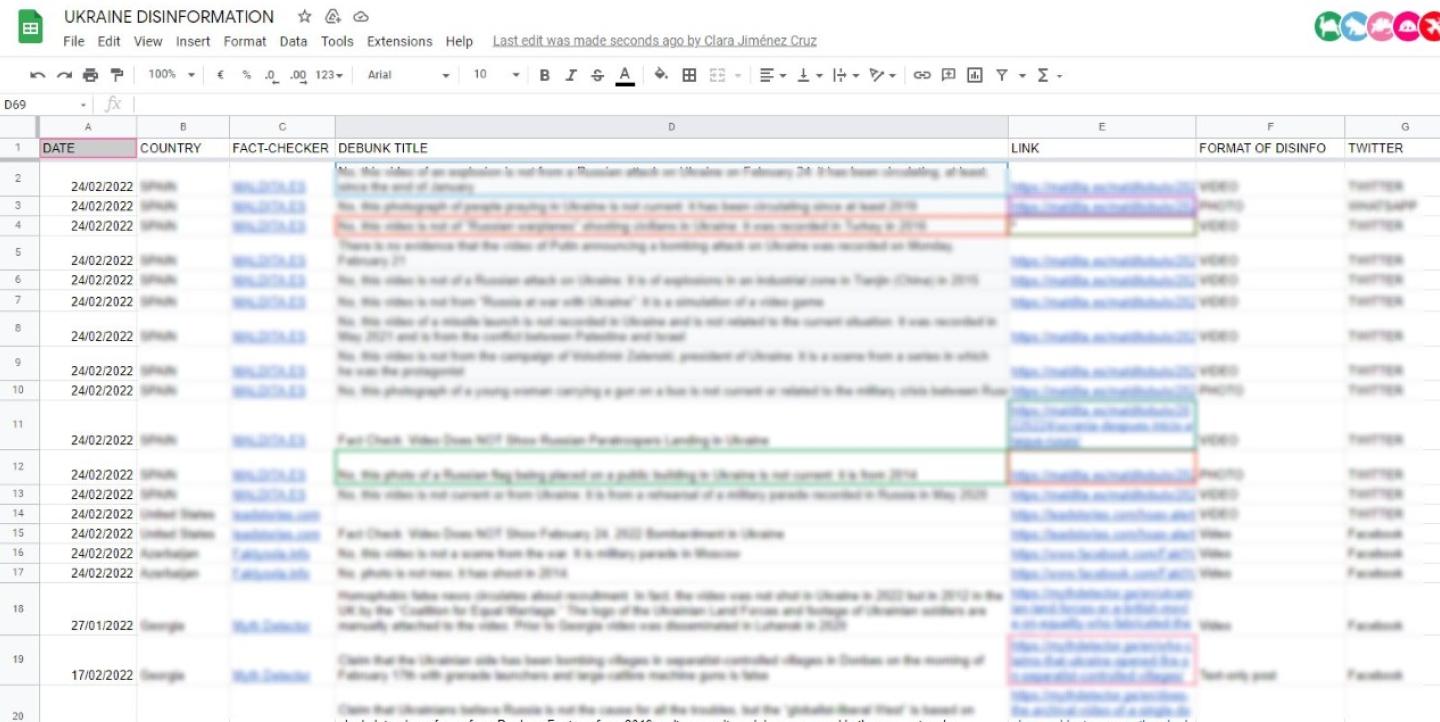

In an effort to document and expose questionable videos and news on social media — including content from Russian state media — the investigative team at Bellingcat put together a spreadsheet last month to help journalists track misleading information and videos online.

Identifying misinformation is challenging because it might contain elements of truth or partial facts, which are taken out of context, leaving them with an entirely different meaning. To avoid this trap, journalists can use the Youtube Data Viewer, a tool developed by Amnesty International, to find websites that might have copies of the same video content they are viewing.

Journalists can, in addition, determine where or when a video was made by looking for visual clues, such as store signs, street nameplates, specific architectural designs, furniture items, traffic lights, plants, vehicle registration plates, or the weather.

Falsified photos

False photos also circulate widely on social media. This included one recently that showed Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on the battlefield. A simple reverse search showed that the Ukrainian government had published the photo of Zelensky’s visit to the Donbas region in April 2019.

Reverse image searches are helpful as misinformation can often stem from photos taken out of context. This method enables you to use a search engine to identify a photo, or a screenshot of a video, and find its source. You will be able to find the source(s) that previously published the image, as well as the publishing date and location it was taken.

Journalists can run a reverse image search using Google Images, Tineye, Bing or Yandex. If you’re using Google Chrome, you can right-click on the photo and select “Search image with Google Lens,” which leads you to the original photo, its date of publication, and location.

Alternatively, journalists can use Who Posted What to find the original photo and its posting date. To do so, copy the photo link into the site’s search bar. You can also search for posts here by keyword within certain time frames. The site allows you to identify the user behind the photo or post, which you can then use to search for their contact information to reach them directly if you have questions about what they’ve shared.

When dealing with issues of which you have no prior knowledge, conducting an internet search is not enough. In these cases, seek help from other journalists. Inside Newsroom, for instance, has put together a list of over 200 reliable journalists covering the war on the ground who you can follow, or reach out to.

Misleading claims and quotes

To identify misleading claims or quotes, first try copying the text in question into a search engine. You may find that it was already posted online prior, or whether it came from another source altogether.

In light of the high levels of mis- and disinformation, ICFJ Senior Program Director Cristina Tardáguila tweeted about fact-checkers’ efforts to expose the false information that is circulating. Journalists can follow the hashtag #UkraineFacts to learn more.

This guide from The Washington Post is another helpful resource for journalists and other internet users to expose manipulated video content. The resource was put together by The Post’s senior producer Nadine Ajaka, who specializes in video platforms, along with fact-checker Glenn Kessler and visual forensics video reporter Elyse Samuels.

Journalists can also verify information and sources online using the following tools:

- Web Archive: If the video is false or has been deleted, you can use this tool to find the original page.

- Fake News Detection Details: This machine model offers “stance detection,” in which it assesses the credibility of claims.

- FactCheck.org: This site allows users to ask questions about the accuracy of political news, while the team provides fact-checks and explainers.

- Pic2Map: Journalists can use this tool to read a photo’s hidden data and find out where and how it was taken.

- Forensically: Journalists can use this tool to expose fabricated photos and the exact parts that were modified.

To learn more about the basics of verifying information, you can check training resources like UNESCO’s Journalism, fake news & disinformation handbook, and the European Journalism Centre’s Verification Handbook.

For Arabic speakers, this tool from the Open Source Handbook offers 25 resources for covering war and armed conflict around the world, including a map, tracker and live updates on the Russia-Ukraine war.

This article was originally published by our Arabic site. It was translated to English by Nada Ramadan.

Main image was first published by ICFJ Senior Program Director Cristina Tardáguila on Twitter.